This article describes various approaches idea-stage startups can take to build a Minimum Viable Product (MVP).

The status quo

You have a startup idea that has been validated. This means that the problem statement is clear, the initial customers have been identified or secured and some signals for willingness to pay have been received.

The next step is building a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) to validate your idea. This article describes various approaches you can take to build your MVP and provides a rubric to help you decide which approach is the right one for you.

Purpose of the MVP

The purpose of the MVP is to get rapid customer feedback on the viability of your idea. The MVP helps you test out what customers actually value as opposed to what they say they value. The MVP reveals the real customer pain points. The MVP will test your hypothesis of the customer needs. You could be off the mark and that is fine — the whole point of the MVP is to start at some point and iterate until you identify what the customer is actually willing to pay for.

By MVP, I mean the initial versions of the product that you put in front of potential customers. It is generally a prototype that solves the most pressing customer needs that have been identified.

Mindset — building a flywheel of iterations

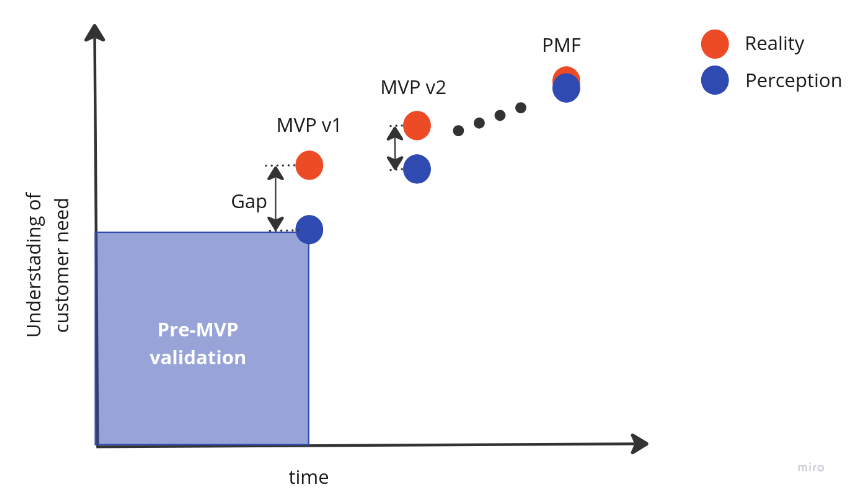

Before starting to build the MVP, adopting the right mindset is crucial for success. The idea and customer validation you’ve done up to this point is about to be put to the test. There is a gap between your perception/understanding of the customer needs and the reality.

Building MVP is a race to reduce the reality-perception gap of understanding and meeting customer needs

Building MVP is a race to reduce the reality-perception gap of understanding and meeting customer needs

When you are reasonably confident that this reality-perception gap is small enough, you start building the MVP to test it.

In this phase, you should optimize for fast iterations: the first version of the MVP should ideally go out in front of customers ASAP. Incorporate their feedback to deliver the next version soon after. Then continue iterating and delivering increasingly refined MVPs that slowly reduce the reality-perception gap. Once this gap is completely eliminated, you have achieved Product — Market fit. This could take a few months, a few years or never happen.

Approaches to building

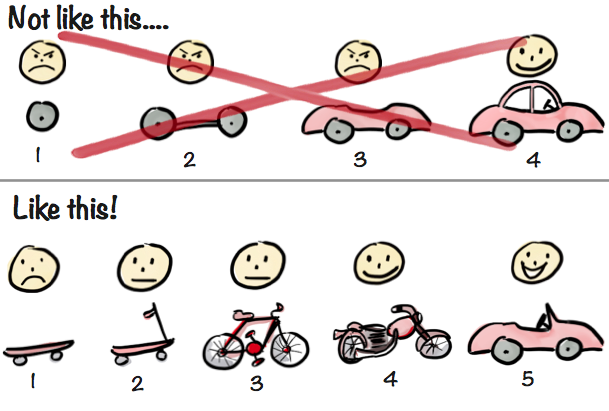

Broadly there are four approaches to building an MVP to test your startup idea. An approach describes Who builds the MVP and How it is built. The What part of the MVP is an entire topic that warrants a dedicated post but here is a great in depth explanation from the creator of the Spotify model.

Start with building a Minimum Testable/Usable/Lovable Product. Source: Henrik Kniberg

Start with building a Minimum Testable/Usable/Lovable Product. Source: Henrik Kniberg

The below approaches to building an MVP apply to both technical and non-technical founders/founding teams. They also apply to solo founders. We’ll first describe the approaches and then compare and contrast them. Finally, we’ll provide a rubric for selecting the approach that’s best suited to your situation.

- Build it yourself (bootstrapped): The obvious and preferred choice if you have the necessary skills and no external funding. It is sometimes the only choice if you are on a limited budget or want to be bootstrapped. This is the best and default option for solo technical founders, bootstrapped founders, indie hackers or technical founding teams.

- Freelancers: If your budget is insufficient to afford a dev shop or if your MVP is not well spec’d out (i.e. you are expecting a lot of changes/pivots), hiring a freelancer or a team of freelancers can be a viable approach to building your MVP. This does require a technical person to manage the freelancer(s) which could be a challenge for solo founders. In such cases, getting on a fractional CTO specializing in very early-stage startups can be a great value add.

- In-house tech team: If you have the resources to onboard early engineers to build the MVP, this is a great option as it allows you to move fast, iterate and adapt quickly. Unfortunately, this option is a luxury available to a very small number of founders who are lucky or privileged to obtain funding before building any product.

- Dev agency: Software development agencies are a good option if your MVP is well spec’d out and you have the budget in the mid-5 figures USD (at least). A whole industry of contract and service based software development companies exists to serve different niches, budgets and engagement models. The key deciding factors are cost, quality, proximity (on-shore, near-shore, off-shore), specialization, trustworthiness and track-record.

Decision criteria

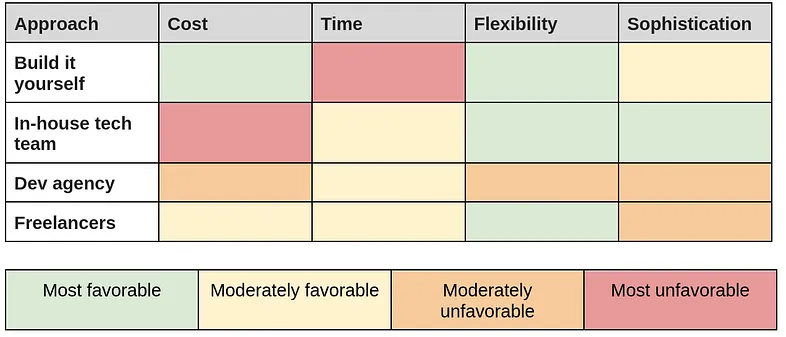

Some criteria to decide between the aforementioned approaches to build the MVP are:

- Cost

- Time

- Flexibility

- Sophistication

Cost is easy to understand and depends on the available budget. Time is closely related to cost as the longer it takes, the more it costs. Time is also critical when it comes to fast moving, crowded markets where the customer needs evolve and competitors abound. Flexibility is related to your understanding of the customer needs: the less you know about what the customer will actually pay for, the more flexibility you need in the development of a solution. Sophistication captures the complexity or finesse required to build the MVP.

Picking the right approach

Picking an approach to build your MVP is determined by the aforementioned decision criteria. If you want to build something:

- Fast, cheap, well-defined and simple → build it yourself (potentially with low-code platforms if suitable).

- Reasonably quick, cheap, not so well defined and not too simple → go with freelancers

- Reasonably quick, reasonable budget, relatively well defined and fairly complex → use a dev agency

- Slow, sizable budget (ex. External funding), ill defined and complex → set up an in-house tech team.

The rubric is shown in the table below.

Qualifying MVP building approaches

Qualifying MVP building approaches

Conclusion

There are several approaches to building your MVP with different trade offs. Pick an approach based on the constraints i.e. decision criteria that are apply to your situation. Picking the wrong approach will possibly sink your business. Picking the right approach but the wrong team will slow you down considerably. Having a strong technical co-founder almost always insures against these two outcomes. Depending on the situation, you can always blend two approaches if advantageous. For example, supplement an in-house tech team with freelancers to save on costs at the expense of speed of development.