Startups are hard. Deep-tech startups are harder. There is an added element of technical risk along with market, regulatory and financial risks. The time to market is several years making it crucial to balance customer and product development with the technology development. Note that what is deep-tech today may not be so in the future as the technology matures.

A moat is your startup's defensibility — i.e., your business's ability to maintain a competitive advantage to protect long-term market share and, therefore, make more profits.

All this means that deep-tech startups require greater upfront investment compared to other startups in order to become successful businesses. However, raising sufficient initial capital is conditioned on many factors, some of which are beyond the control of the founding team. Hence, we focus on a scenario where a deeptech startup has to execute after raising very limited capital. What follows is a recipe for commercializing a deep-tech startup idea with very limited resources. Like any recipe, it is not to everyone’s taste and it only applies given severe resource limitations. Furthermore, this is a complete recipe, described at a high level. Each step of the process can be dissected into detailed strategies and concrete tactics. This might be done in future posts.

Pre-requisites

- A founding team that is 100% committed to the process of startup building

- Complementary skills and deep domain knowledge amongst the founders.

- Access to highly-skilled low-cost talent

- Determination and resilience. Lots of it.

- A scrappy mindset for doing anything.

- Ruthless focus on execution.

Method

Step 1: An idea is born.

The first step is the birth of the idea itself. These are typically developed in an academic or industrial research environment.. It starts with one or more scientific discoveries or engineering innovations that may have several promising practical applications. The applications may not be immediately obvious at the time of discovery. The founding team must have had a direct exposure to these environments and understand the gaps in the science or technology that need to be filled in order to commercialize the technology.

Step 2: Map out the market opportunities

If the commercial application is not immediately clear, spend some time doing customer discovery to understand the market for the various applications of the technology. This is a very tricky phase since the market for deep-tech doesn’t exist yet or is in the nascent stages. Customer interest is muddled since there is no product out there for them to test. A classic chicken-and-egg problem. The key here is to understand which customer(s) have a hair on fire problem. As Michael Siebel puts it, if your friend was standing next to you and their hair was on fire, that fire would be the only thing they really cared about in this world. In other words, the customer is desperate for a solution to this problem and will trial a half-baked proof-of-concept (PoC) if available.

Your customer with a hair on fire problem

Your customer with a hair on fire problem

How exactly do you know if the problem is a hair-on-fire problem? Some proxy signals:

- The customer is losing a lot of money every day/week/month due to the problem and lack of effective solutions

- The problem presents an existential threat to the customer

- The customer has spent a lot of money trying out different solutions (internal/external) to the problem

Try to estimate roughly how many such customers are out there and the total value of this market segment. The use-case can and probably will change over time as the market develops. **The key here is to understand common customer pain points and their associated monetary value and roughly size each market segment. **

An example (with made up numbers): Consider a new process of generating artificial meat that can shave off 90% of the cost of producing real meat. If the total market for meat manufacturing is 100 billion USD, this technology can unlock 90 billion USD of value.

During this exercise, you will likely uncover many promising market segments or even completely different markets. Size each market segment based on all available knowledge (an art in itself)

Step 3: Assess the market readiness and product complexity

You’ve identified the market segments in Step 2. Now it is time to understand which market segment is the easiest to enter. Markets have many barriers to entry: competition, regulations, sluggishness due to incumbents etc. As a young, underfunded startup, it is crucial to know which market segment is easiest to commercially operate in. The way to concretely gauge this is through LoIs from prospective customers. The LoI should ideally state explicit demo requirements that could lead to a paid pilot.

Each market or market segment will likely have different technical and product requirements. In the case of deep-tech, this is usually a prototype which solves the main problem faced by customers in that segment. Product requirements dictate the complexity of the product which directly translates to how long it will take to build the Minimum Viable Prototype (MVP). Remember, that this is not a mobile or web application or SaaS that can be built quickly with the right resources. Also recall that we are underfunded, which means there is no luxury of hiring very expensive expert teams. Hence it is desirable to identify segments where the MVP is less complex.

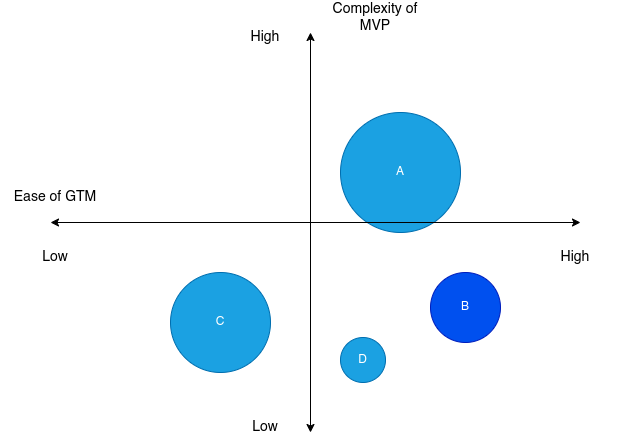

Map out the market segments based on the ease of their Go to Market (GTM) and the complexity of building the MVP as shown below:

Pick markets where you can quickly build and commercialise an MVP

Pick markets where you can quickly build and commercialise an MVP

We want to stay in the bottom right quadrant where the product complexity is low, the GTM ease is high and the market size (denoted by the size of the circles) is reasonably large. In the figure, B seems like the best market segment to go after. D could also be promising. A will need a lot more time to build the MVP and C will be difficult to commercialise.

In reality, which market to address first will not always be crystal clear and will need some smart prototyping, industry knowledge and the ability to pivot quickly.

Step 4: Build the MVP. Fast.

This can take anywhere from a few months to a few years. Focus on building the core functionality first. The core functionality is the set of features that will meet the minimum demo requirements outlined in the customers’ Letter of Intents (LoI). Building anything more or different is likely to be a costly mistake. Remember that the MVP will undergo several iterations and rewrites so speed is of foremost importance. Another important aspect is the clear demonstration of value which comes down to the core feature(s) i.e. the hard to build innovation that solves the customer’s hair-on-fire problem.

To minimize the cost of building the MVP, harness your professional and personal contacts and wider industry and academic networks. This can take various forms:

- University labs to build and test initial prototypes using highly qualified human resources. These come with added complexity of elaborate IP licensing agreements.

- Startup incubators and accelerators to find motivated and talented technical people who can advise, assist or be actively involved in various stages of the MVP building process.

- Research or startup funding grants from Government or public sector organizations which can fund part or all of the MVP building costs.

- Remote talent in the form of expert consultants or just highly skilled technical people who may not be available or affordable in your location.

Step 5: Deploy the MVP and iterate.

Once the MVP is ready, deploy it to the customers and start getting feedback. Depending on how many simultaneous PoCs you are running, you should parse and prioritize customer feedback and integrate it into your product roadmap. Customers don’t always know what they want especially when it comes to new products and services. Hence, it is important to categorize customer requirements into nice to have, wishlist, necessary and critical. Understand the why behind every customer feedback. Prioritize the backlog towards features that will uncover more insights or value for the entire segment and not a particular customer. There are exceptions to this, for example, when you have a single large customer with a strong interest or potential to convert into a high value pilot. However, be wary of being tied down to that one customer and becoming a consulting house. While there is nothing inherently wrong with this, it does not enable the creation of a high-growth, high-value technology company in the long run.

Do not blindly follow customer feedback (image source)

Do not blindly follow customer feedback (image source)

Step 6: From prototype to product

The final step in the recipe is to build a true Minimum Viable Product from the prototype. Depending on the GTM and product strategy, this will require varying amounts of non-core product engineering to be built around the core features. To do this on a limited budget requires access to low cost highly skilled talent.

Opportunities are unevenly distributed but talent is not.

The COVID pandemic has made remote work accessible and critical to work with the best talent around the globe. Managing remote teams effectively and efficiently to deliver product engineering helps keep costs low without sacrificing on quality. Furthermore, this sets the company up for future expansion into different geographies.

And that’s it. A recipe for building a deep-tech startup on a shoestring budget.

I’ve glossed over several details in lieu of providing a full view of the process. Additional posts diving into the details frequently encountered in the startup journey will follow. Feedback and questions are most welcome.